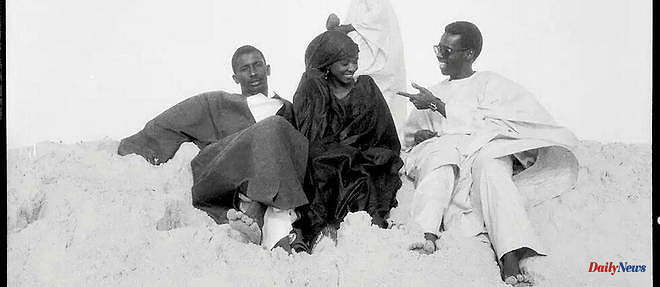

As a duo, the Parisian galleries Talmart and La La Lande have decided to exhibit for a month* Adama Sylla, a photographer not quite like the others. Title of the exhibition: "The Poetic Mechanics of Adama Sylla". A first in the city of light for this man born in 1934. An archivist by profession, Adama Sylla has documented daily life in Senegal with his camera from the dawn of independence to the present day. The opportunity to keep alive the memory of his country with in mind that "the daily life of today is the history of tomorrow". Fundamental Institute of Black Africa created by the naturalist, explorer and scholar Théodore Monod, World Festival of Negro Arts in 1966, Saint-Louis from the 1970s: places and key moments that inspired him as much as encounters with illustrious personalities such as Academician Léopold Sédar Senghor, Professor Assane Seck, President Abdou Diouf, among others, with everyday men and women, witnesses and actors of the upheavals that have marked Senegal over the past 50 years . "In the footsteps of St. Louisians Meïssa Gaye (1892-1982) and Mama Casset (1908-1992), Sylla's work highlights the modernity of Senegal's predominantly urban forms," explains Marc Monsallier, gallery director Talmart.

This probably explains why the work of this contributor to the book L'Anthologie de la photographie africaine by Frédérique Chapuis, published by La Revue Noire (1998) and winner of the Niepce Prize, has been the subject of fine exhibitions, first at the Rokhaya studio in Saint-Louis du Senegal in 2017, then at the Galerie du Fleuve of the French Institute, still in Saint-Louis in 2019 as part of the inauguration of the Villa Saint-Louis Ndar de l French Institute, at the Women's Museum Henriette Bathily in Dakar in 2020, at Regard Sud Galerie in Lyon in 2021 and finally in Paris at the moment with curator Ange-Frédéric Koffi, a young artist photographer born in Korhogo (Ivory Coast ), a graduate of the École cantonale d'art de Lausanne (ECAL, Switzerland), nominated for the 2022 FOAM awards (Amsterdam, Netherlands) and a recent resident of Zeitz Mocaa (Cape Town, South Africa). He shared his childhood between the African continent (notably Saint-Louis of Senegal), Europe and Asia and has just completed his first personal exhibition in Abidjan: "Territoire des perceptions, Sérénade des Formes", at Cécile Fakhoury. For Le Point Afrique, he agreed to talk about Adama Sylla and his work.

Le Point Afrique: Who is Adama Sylla for whom you curate the exhibition?

Ange-Frédéric Koffi: Adama Sylla has a work that is very different from the photographers we know, Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta, but which gives an extremely important insight into African society and especially Senegal in the 1960s. How society lived just after independence; how it has changed in its mores, but also how it has become a little Americanized with the music, the clothes; how have the transformations of Senegalese society taken place in its way of life. Otherwise, Adama Sylla has a massive database of 40,000 draws and has shot a lot. In his relentless work, he managed to bring out an aesthetic that is unique to him, a writing that is very reminiscent of what can be found in Europe. It has a lot of curves that are reminiscent of a classic culture. It is important to underline this and to highlight this tenacity to persevere in photography at that time.

He is an archivist by profession. Do you feel an archivist's approach in his way of working, of approaching his city, Saint-Louis du Senegal, and the inhabitants he meets there?

Totally! We feel it in this urgency to constantly capture what is happening around him. I invite the public, in the way the exhibition is presented here at the Talmart gallery but also at the La La Lande gallery, to have an aesthetic, but also ethnographic and anthropological look at the images. He has, through his recordings, been able to highlight patterns of fabrics, headdresses, clothes, objects that are important to look at to understand how society has evolved, and to keep track of it. He does this consciously, but also unconsciously in his relationship to photography. This accumulation of images is just impressive.

What is the appreciation that the public has of his activity, of his initiative?

This leads to wondering about the prism: are we talking about local people living with him or people who live here in Paris and discover his work?

I am thinking of the Senegalese who rub shoulders with him regularly and then of those who look at his photos here in Paris.

I noticed, because I went with him to Guet Ndar, a neighborhood of the language of barbarism in Saint-Louis, that he is a character known to everyone. He can walk around pretty freely and take pictures of everyone because that's what he's been doing for fifty years. It is in this dynamic to capture the energy of people who tell you that they have known him since they were very young. I'm impressed, because these people are my parents' age. It's really moving to see that. In Senegal, he went under the radar, but in Saint-Louis, we know him very well. For the daily significance of documenting people's lives by taking pictures of them in his studio. Also in the events he attended. So wrestling matches, marriages, etc.

As for here in Paris, the way he is received is extremely interesting. You should know that we have a very fragmented vision of photography in Africa. There is a West African center very focused on Mali, then a small school of photography in Nigeria. Afterwards, we dive directly towards South Africa. The relationship to photography is very different there, notably with questions of archiving linked to apartheid, a system that relied heavily on documentation.

In West Africa, when you put it in context, there is a notable fact in relation to Malick Sidibé or Seydou Keïta. Adama Sylla is not in this approach of the studio where we will invite people to perform. We are in a certain staging, but his studio is stripped. The staging is more in the characters than in the sets, in the way people will come to pose, look at the lens, the way also in which he has built his relationship to the image, his relationship to lines, to curves . Between the off-screen, the first shot and the second shot, there are a lot of elements that appear and which radically differentiate him from other West African photographers.

What is its relation to memory?

Adama Sylla is aware that you have to keep as many things as possible, but he is not in a neurotic relationship with memory either, because the light that gives the image ends up taking it back. He dutifully guards his dandruff, but with the environment of sea salt, heat and weather, it's not easy. This made it a little more difficult to keep the prints for cost reasons, but also for technical reasons. That said, he is truly in a momentum to keep.

You still have to remember that at the end of the 1970s, many studios in Senegal and West Africa went into decline. Despite this, he kept a good number of what he had. He is aware of the need to preserve images, as he has saved a large number of rolls of film. When we go to his studio, we see a large number of images that he has kept in albums. It is therefore very interesting to see how his work as an archivist pursues him in his relationship to the image and in conservation.

How does it relate to technology and the evolution of photographic equipment?

I think he's rather averse to technological advancement or rather digital. It's true that he has an analogical relationship to the image and to the film. His report is extremely purist to the image and all the questions that arise from it. It does not necessarily have a metaphysical relationship with materiality and the different image treatments. He doesn't shoot, he doesn't develop with a conscious relationship to the materiality of the images. That said, he is aware of it and will photograph to keep the images that are important to him. Today he has digitized a number of his photos, but there is still a lot of work to be done for as complete a backup as possible. He is aware of it and he is in this dynamic. I think we need a grant and external aid to better meet the costs.

In the exhibition dedicated to him, what are the themes highlighted, the lines of force that you want to see perceived and retained by the public?

There are two things: first, an aesthetic aspect that stems from my own relationship to art. This is also why Marc Monsallier, director of the Talmart gallery, in the 4th arrondissement in Paris, asked me to curate this exhibition. I must say that my master questioned my practice as an artist and also as a curator on the way in which we receive art and design from the African continent, that is to say all the questions of scenography and display that will result. There is still today in the presentation of productions from the continent a strong anthropological and ethnographic relationship. And that bothered me in the two previous exhibitions that I saw on Adama Sylla.

I would say that in my proposal here, the issue of margins has been questioned. Why do we make a photo with a large margin, with a passe-partout, with a wooden frame? In the historicity of exhibitions, this has a weight and it forces the viewer to perceive and receive Adama Sylla's work through a prism that bothers me. Suddenly, if you look at the images of our exhibition, we are in a different relationship to the image and not in the margins which are important. Large formats do not have a margin, a master key, and the format that was decided for the smallest photos was that of the Polaroid for a transmission issue.

This means that the different axes that are in the exhibition are, on the side of the Talmart gallery, a series that will deal with studio photos, a series that will deal with night photos transcribing the energy of the city, a series which will deal with daily shots of images and in this series of daily images there is an interior section and another exterior. On the side of the La La Lande gallery, there is a focus on the series of wrestlers that he also made in the 1970s and 1980s. And in the basement of the gallery, we invited a Tunisian artist, Ilyes Messaoudi, who reacts and responds to the work of Adama Sylla, but with the practice of painting on glass upside down which is proper in Senegal. We invited him to see if a form of dialogue could arise. I find it extremely interesting to give back to Sylla its historical side, but also very important to update it through a contemporary artist and his productions.

What is the thought you want the public to have after seeing this exhibit, the thought that would make you feel like it did well?

What is important for me is to underline the singularity of Adama Sylla's work, and to show the relentlessness he had in his practice of photography on a daily basis. That the culture of Adama Sylla, radically different from that of the Malians that we know, namely Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta, be perceived. He has a historical relationship with the various photographers known in Senegal such as Mama Casset, but he has a style of his own. What I hope is that the public will have immersed themselves in the images to see the singularity of each photo, that they will not have had a distanced relationship, but rather a very intimate relationship with each of them. .

* Until April 22, 2023

Participating in Adama Sylla's "Poetic Mechanics" exhibition, Ilyes Messaoudi is a visual artist and designer born in 1990 in Tunis and who lives between France and Tunisia. Trained for two years at the Ecole Supérieure des Sciences et Technologies de Design de Tunis (ESSTED), he owes his presence in this exhibition to his ability to renew the art of the coaster, a work he has exhibited and edited through his series "The loves of Antar and Abla". Accustomed to devoting his creation to female characters, he exercises, within the framework of this exhibition, his inverted gaze, as required by the practice of coaster, in dialogue with scenes of wrestlers seen through painted glass. What to bring more to the subtle mix of genres, combining painting on canvas and coaster, collage, embroidery and sometimes text which makes its signature in the representation, with humour, of the Tunisian woman of the 21st century, "with its modern worries , its differences with men and the restrictions of contemporary society”. Since 2016, between Paris and Tunis, he has had seven personal exhibitions.