Officially dedicated to the fight for women's rights, the day of March 8 is sometimes misunderstood, especially by those who wish a "Happy Women's Day", a red rose or a box of chocolates in their hands.

It also happens that some people question the relevance and the merits of this day, for example by affirming that "in France, professional equality is acquired", or by calling for "an International Day of Human Rights". . Here are some arguments and figures to oppose these assertions.

Established in 1977 by the United Nations (UN), "International Women's Day" is celebrated in many countries on March 8. A name also used by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) or the European Commission. In 1982, Yvette Roudy, then Minister Delegate for Women's Rights, led France to recognize March 8 as "International Women's Rights Day".

But every year, some people call it "women's day". With, as a bonus, the endless marketing and sexist operations touting nail polish, "chocolates reserved for women" or bouquets of flowers.

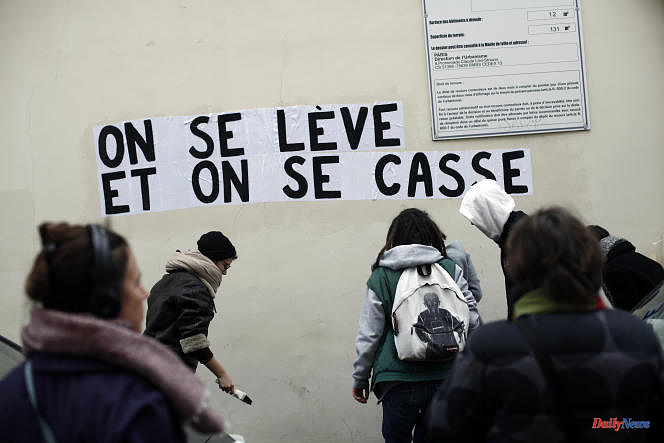

However, this day was created in a militant perspective. It is an opportunity to reaffirm the importance of the fight for women's rights and to pay tribute to the fights, past and present, carried out in favor of gender equality. "March 8 is not International Women's Day, the day we give away bras, but International Women's Day. The right not to die under the blows of one's spouse, for example", recalled in 2019 the feminist collective

It is therefore neither a second Valentine's Day, nor a day aimed at celebrating "the woman" - the singular highlighting a "feminine essence", as if there were only one way of being a woman or just one model of femininity. "'The' woman does not exist. There are millions of us,” summarizes feminist activist Caroline De Haas.

“Work of equal value, equal pay. This principle has been enshrined in the French labor code since 1972. However, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (Insee), whose most recent figures only take into account the private sector, women earn on average 16.8% less than men in full-time equivalent, i.e. for the same volume of work.

Added to this are inequalities in the volume of work, women being much more often part-time and less often professionally active during the year than men. When all of these factors are taken into account, they earn on average 28.5% less than men.

In addition, although they now have more qualifications than men, there are fewer women in management positions. The glass ceiling is still a very strong reality in business. Admittedly, there is better on the side of the boards of directors, since the Copé-Zimmermann law (2011) imposes a quota of 40% of women on them. But they are barely more than 20% on executive committees, while 37% of companies still have fewer than two women among the ten highest earners and only one CAC 40 group, Engie, is headed by a wife, Catherine MacGregor.

True, but in what proportions? Women remain under-represented in certain professions even if, in theory, nothing prevents them from having access to them. This is the case, for example, in the wine trades, in the IT sector and more broadly in scientific fields.

While France ranks first for the level of education of girls, according to the 2017 report of the World Economic Forum, only 27% of female students are in engineering training. A paradox that is largely explained by gender stereotypes. In the end, women are directed towards so-called feminine professions and find themselves deprived of access to careers with responsibilities, better paid or valued.

In politics, the place of power par excellence, despite the parity law of June 2000, the account is still not there. Women are only 35% in the Senate and 41% in the National Assembly. In addition, 80% of town halls are headed by a man. Edith Cresson is the only woman to have served as Prime Minister and her tenure was one of the shortest under the Fifth Republic.

On average, French women devote 3 hours 26 minutes per day to domestic chores (housework, shopping, child care, etc.) compared to 2 hours for men, according to INSEE. While this gap tends to narrow over time, progress is very slow. "At the current rate, it would take decades to achieve a balance in terms of the sharing of domestic tasks between men and women within the couple", underlines INSEE.

Added to this is the household "mental burden". This concept, developed in 1984 by the sociologist Monique Haicault, refers to the time devoted – in the vast majority of cases by women – to organizing housework and life in the home. It is the fact, for example, of having to ask your companion to hang up the laundry. However, having to manage these thousand and one small tasks ends up weighing considerably on the mind. In May 2017, blogger Emma helped popularize the term via a comic strip posted on Facebook and shared hundreds of thousands of times.

In terms of gender equality, France ranks 15th out of 153 countries, according to the 2020 report of the World Economic Forum. A worse place than in 2018, when France was 12th. Moreover, it is doing better than most countries, but the situation of women is far from perfect.

In 2019, 146 were killed by their spouse or ex-companion; and according to the "Living Environment and Security" survey, in each year from 2011-2018, 62,000 were victims of rape. According to an IFOP study published in 2018, nearly one in three women (32%) has already been confronted with at least one situation of sexual harassment in the workplace.

In addition, France's position on gender equality should not make us forget that March 8 is indeed the International Day for the Fight for Women's Rights. It is therefore also an opportunity to show solidarity with the fights waged abroad: the right to abortion in Poland (drastically limited in October 2020) or in Honduras (prohibited in all cases), for example.

While the fights started in the 1970s are not all over, others have emerged over time: the fight against street harassment or against menstrual poverty, the use of egalitarian writing, the fact of get rid of the injunction to remove hair, etc. So many issues which, according to some, would not do justice to the great battles fought by their elders, or even which would be unworthy of feminism.

Another argument invoked: these fights, considered secondary, would divert society from the "real" problems, such as wage inequalities or domestic violence.

By tackling all of these themes, the new generation of activists conversely affirms loud and clear that there is no small feminist fight. For them, it is not by prioritizing discriminations that they will disappear: everything contributes to the fight against sexism and the system of male domination.

Prostitution, wearing the veil, surrogacy (GPA)… Several themes are indeed the subject of passionate debate between feminists. What we usually call "feminism" is actually multiple, plural. It is part of a set of currents of thought and intellectual representations. These disagreements – whether philosophical, political, militant or strategic – are not recent.

Above all, they are simply inherent in the debate of ideas. Would the political class be blamed for being divided on many issues? Of course not. It is not uncommon to see controversy emerge within the same party. Some would say that these controversies, sometimes very lively, precisely make it possible to better feed the reflections. The same is true within feminist movements.

In fact, this day has existed (November 19) for about twenty years, but it is not recognized by the United Nations. The date was chosen by Jerome Teelucksingh, a university professor in Trinidad and Tobago, in honor of his father, who was born on November 19. However, the objectives of this day are quite vague and it remains little known.

Above all, as one netizen pointed out, on March 8, 2019, men are asking this question – why is there no International Men's Day? – “Only on International Women’s Day (…). Like they don't care about International Men's Day, except for International Women's Day."

The real question to ask would rather be: why, in 2021, do we still need an International Women's Day? Quite simply because women still do not have the same rights as men in a universe marked by the systemic dimension of patriarchy.