Two fingers raised to form the "V" for victory. But two fingers with red tips, the color of menstrual blood. The poster for "Free Menstruation", West Africa's first festival dedicated to menstrual hygiene, organized by the NGOs Actu'Elles and Gouttes Rouges in Abidjan on Saturday 27 and Sunday 28 May, had something to challenge. During this event, an awareness panel was devoted to the specific issues of menstrual health in prison, largely neglected by the Ivorian public authorities.

"When you arrive in prison, you have nothing, testified Viviane L. W., a slender forty-something who has behind her two stays in detention, in 2007 and 2018. No toothbrush, no sanitary napkins, no underneath, than the clothes you were wearing when you were arrested. There is no shop in prison, no one who will go and buy this for you. For inmates like Viviane L.W., resourcefulness is what counts.

It is then necessary to be satisfied with a cloth, an old rag, a piece of torn loincloth... Makeshift protections difficult to clean and dry correctly in the cramped cells, where space and household products are lacking. Overcrowding, coupled with poor hygienic conditions, frequently leads to infections, which can have serious consequences.

"Bleeding"

And the risk is not only health: the taboo of menstruation persists even in the cells. He is the cause of frequent fights. All it takes is for a periodic rag to touch the loincloth of a fellow prisoner on the dryer for tempers to flare. “Over there, there is no small fight, comments Madoussou Touré, the president of the NGO NGO SMED-CI, for Support for mothers and children in distress in Côte d’Ivoire. When the first blow is struck, it goes to blood. »

Menstrual hygiene in the prison environment is the workhorse of this association that the young woman, a lawyer by profession, carries at arm's length. “There is a problem of menstrual precariousness when you are a woman in Côte d'Ivoire. So can you imagine what it's like to be behind bars? “Always well dressed, with a soft voice, without condescension, Madoussou Touré has been tirelessly collecting batches of sanitary napkins from private donors since 2021. She then sends them to Ivorian prisons, where the female prison population is largely invisible.

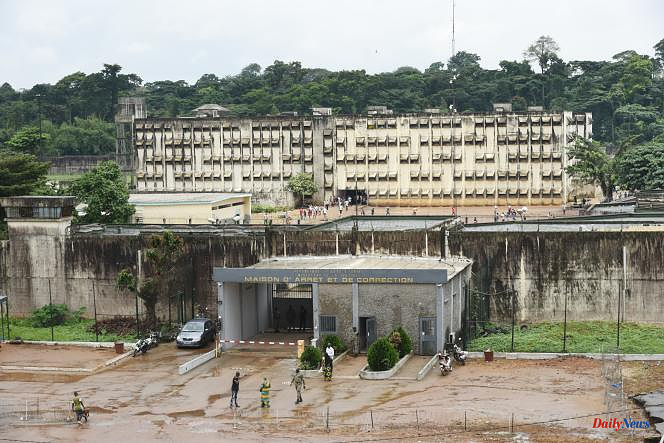

First of all, there is an explanation linked to the rare numbers. In the last survey carried out by the National Human Rights Council at the beginning of 2021, some 448 women were imprisoned in Côte d'Ivoire (CNDH), half of them awaiting a first judgment. The Abidjan House of Arrest and Correction (MACA), the largest prison in the country, built in 1980 in the commune of Yopougon and originally designed for 1,500 prisoners has more than 10,000, of whom only 300 women, who live in separate quarters. Periodic protections are not provided. "The State of Côte d'Ivoire intervenes for food and medicine, but gender-specific needs are not taken into account, regrets Madoussou Touré. Being in prison is already a punishment, but for women who menstruate there, it's double punishment. »

In Ivorian society, the very existence of female criminals is another taboo. “Crime has no gender,” says Ms. Touré, and the Ivorian authorities apply this popular saying to the letter. "The prison environment was not designed for women," confirms another volunteer who works in the prison environment, sister Emmanuelle of the NGO Ivoire et Sourire. From her small office located in Bingerville at the entrance to a town on the edge of Abidjan, the nun remembers having seen the penal establishments adapt as best they could to the arrival of women behind bars. "There are still far too many of these women for the space allocated to them," she said. At the remand center in Aboisso, a town located about a hundred kilometers from Abidjan, where Sister Emmanuelle operates, 14 prisoners share a single cell, in the middle of the men's prison.

"They are not animals"

NGOs are not the only ones to want to warn about their situation. “We must come to the aid of our women prisoners, insists the Ivorian lawyer Me Roselyne Aka-Serikpa. Whatever offense they committed, however serious it may have been, they are human beings, they are not animals. “She who has defended both men and women knows the fate of her clients in prison. "Detention is the extreme sanction in criminal matters," she recalls. But it is made to teach the person a lesson and bring him to resocialize. The goal is not to punish for the sake of punishment. »

The most delicate question is that of the resocialization of the prisoners. If the work of associations is so crucial, it is also because many detainees receive neither sanitary protection nor food donations from their families behind bars. Not even, often, visits to the visiting room.

"People's view of me has changed," confirms an ex-prisoner, who passed through Abidjan prison in 2019 for possession of narcotics, and has since been followed by the NGO Doctors of the World. On the terrace of the association's office where she agreed to testify anonymously, the young woman keeps her frail figure straight, but cannot prevent her voice from shaking. Almost all of his family have turned their backs on him, except for his sister. "She was the only one who sent me packages, and who never stopped caring about me," she says, blinking back tears. In Africa, being in prison is already a shame for the family. But a woman in prison? It is an abomination. »