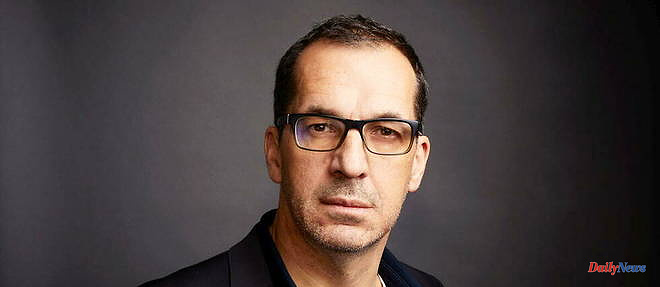

We are not used to seeing Jean-Christophe Grangé, the author of Crimson Rivers, extolling someone else's thriller. Here he is, however, "godfather" of a first-time novelist, Franck Ollivier. The two men met in 2004, during the adaptation of L'Empire des loups by Gaumont, with Jean Reno. They never left each other again.

But it still took years for the screenwriter from Roanne to decide to show the master who had become a friend the novel he was writing in secret. This novel, L'Ombre, which has just been published by Albin, features a writer - evil-obsessed profiler Nicholas Foster, serial killer priest Patrick Hollmann, and FBI investigator Michelle Ventura in the serial killer's favorite land: California. Meeting with the "foal" of Jean-Christophe Grangé.

Le Point: How did you become friends with Jean-Christophe Grange?

Franck Ollivier: During our work on the script for L'Empire des loups, I was trying to convey the spirit of the book, that is to say, to detach myself from reading the novel too literally. It pleased Jean-Christophe, who was immediately confident. Subsequently, we found ourselves around literary and cinematographic references. Common points, like the question of twinning, which I explored in the Zodiac series, broadcast on TF1, and him in Les Rivières pourpres. Finally, a kind of quest for evil common to the things we both do.

I wanted to be a chiropractor! I went to study in the United States in the 1990s and in the American curriculum, you have to do dissection. I spent four months with a corpse! Diving into the human body changes your vision of anatomy. The body was wrapped in a sheet, we lifted only the part of the body that we had to work on, starting with the feet. But there was always a student moron enough to lift the sheet and reveal the dead man's face. It woke me up at night for a long time...

Is that what gave you a taste for crime?

No, it came to me much earlier. I must admit that I missed Asterix and Tintin… Around the age of 12 or 13, I devoured the novels published in the Black Series. Hardcover volumes with a yellow border that my grandfather bought. That's how I discovered Chandler and Hammett.

But then, how did you go from chiropractor to writing?

I've always wanted to write, but writing a novel for me was like climbing Everest alone. Masterpieces are terrible in that they can be overwhelming. The screenwriting turned out to be a good in-between. We write, but in the service of a collective work.

I had taken screenwriting lessons in the United States, where I had been taught how to do index cards. It is thanks to this knowledge that I first entered as a reader in France at TF1. It wasn't like/dislike, I was finding solutions. I accompanied, I injected ideas. That's how I had the opportunity to rewrite a script that had been stuck. It worked. I entered the profession through the window.

The TF1 school doesn't sound very American, even though your novel is set there...

In 1999, I was still at TF1 when I left for California. I went back and forth there, from project to project. This is also how I came across the news item that inspired me Zodiac. In 2012, I moved there with my family. It was for the Jo series with Jean Reno, then Taxi Brooklyn, adapted from Taxi, two series written and produced in the United States. I lived for a time in Santa Monica, for the children's school, then in Westwood, right next to the Federal Building, the headquarters of the FBI, which I could see constantly from my window. One day there was a kind of alert, the fear of an attack. A real wave of panic. It was like in a movie. I loved it. In the United States, we feel that everything can change at any time.

How was your novel The Shadow born?

It could have been a screenplay. Then I wanted to dig deeper into the characters, beyond the action. I felt stronger to get there, finally, after fifteen years in the business, ten years in the script! Especially the writer Foster, expert in various facts. Because he has this dilemma: he makes a success out of a tragic past and that has consequences for him, as a person and as an investigator. Then, other characters joined in, like the investigator and the killer priest.

Does a serial killer priest really exist?

Oh yes. By the way, you should watch the documentary The Keepers on Netflix, about a Pennsylvania priest protected by his hierarchy. One of the first killer priest cases dates back to the 1930s. He is a very inspiring evil figure. I wanted a character tormented by this dilemma, at the same time carried away by his impulses, but who tries to understand them. He is adrift. He's a criminal, but he believes in God.

A very Dostoyevskian character!

Except where Dostoyevsky's characters leave off, my Patrick Hollmann springs into action! And I wanted him to become a founding figure in The Shadow. He is not present in the temporality of the crimes or of the investigation. The killer already dead, fifteen years earlier, but he still kills, because he was emulated. I thought of making his questioning the background of the story but, despite his death, he became frontal, central.

And why then, after years of writing this text, did you suddenly decide to submit it to Grange?

The novel wasn't finished, but after re-reading it, I said to myself: either I stop or I get serious about it. If Jean-Christophe, who is my referent, thinks it's worth continuing, let's go. Otherwise it was over.

The Killer Bit: Patrick Hollmann felt with equal power the presence of God and the need to kill. The realization of this duality had been a disturbing, oppressive, and ultimately overwhelming moment in his life. Resolving this contradiction had been long, complex and painful. He had managed to understand that what might seem like a moral or logical flaw, depending on whether one apprehended it by feeling or by reason, actually bore the superior mark of the divine. This conclusion was the culmination of an intense inner quest, fruit of long hours of prayer, patient readings and rigorous reflection of several years studded with many ferocious crimes. had found no cause for his urges, no original trauma. God knows, however, that he had sought. And searched honestly, for he yearned for nothing more than to penetrate the mysteries of his being. He had suffered no traumatic violence, in memory of course, but he had long and methodically explored the maze of his memories. He had never been touched by evil as society or religion defined it. He had had a happy childhood in a balanced home, between a forester father and a music teacher mother, with a sister two years younger whom he adored with all the more fervor because a congenital malformation of the pelvis had affected her with an irremediable limp. Their family was religious but without this faith being a suffocating blanket. On the contrary, she was a guide who helped him to accept, to forgive, and to move forward in life until adulthood, where his vocation, thanks to the discovery of the infinite power of prayer, was affirmed. in a certain and definitive way like a backfire to his deep loneliness. Without however succeeding in extinguishing his desires for murder. What was this tenacious desire that ran through his veins and fed his brain with faces distorted by pain, throbbing convulsions, screams, groans, pleas, bowels exposed, open, torn, offered, sticky, stinky and bloody? He couldn't tell himself he was a mistake of nature . An avatar. A logic had to be found. A path. It was fifteen long years of sometimes erratic exploration, but which culminated in a certainty now anchored to the body that he would carry to the grave: it was the love of God that had led him to the crime.

Consult our file: Le coin du polar