People are primarily concerned with one topic: energy security. Just talking about the most economical consumption possible is not effective, says Mycle Schneider. What good is electricity or gas if you can't pay for it? "In France, up to 60 percent of energy costs are subsidized," explains the energy consultant in ntv's "Climate Laboratory". If you took this money and renovated the houses, consumption would fall dramatically - and forever. That would be a "reasonable energy policy" that should exist in six areas, says Schneider: "It has to be warm in winter and cool in summer. You need light, cooked food, mobility, communication and engine power." If roof surfaces are designed sensibly and houses, offices, factories and supermarkets are properly insulated, in some cases no energy needs to be used at all.

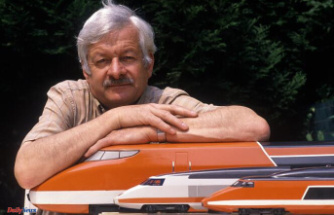

ntv.de: You prefer to talk about intelligent energy services than about energy security. Why?

Mycle Schneider: We always debate kilowatt hours, cubic meters of gas, tons of oil or coal. But basically it's not about energy units, it's about the question of what you can do with it: generate heat, cold and light and, above all, cook food of course.

So it's not about saving as much energy as possible?

A sensible energy policy must ensure that citizens always have access to these energy services, not to gas or oil. It must be warm in winter and cool in summer. You need light, cooked food, mobility, communication and engine power. These are six categories that can be defined.

And that should be considered regardless of how much gas or electricity is used for it?

The key is that as many services as possible are covered in a passive manner. This means, for example, that a house has very low consumption if it is designed sensibly.

Because it's well insulated?

Yes. You can do that so well today that you no longer need active heating at all in winter. And if it's warm in winter, it's also cool in summer. Then you can completely dispense with the question of kilowatt hours. By the way, everyone brings warmth. An architect once told me at a conference about the first zero-energy houses in Sweden. When the thermometer dropped to minus 20 degrees in winter, they called the owners and asked if everything was okay. They replied that they had to open the windows because it was way too warm at their party.

So it's essentially about building houses and other buildings in such a way that they consume as little energy as possible from the ground up?

Exactly. Regardless of the form, as little energy as possible should be supplied. This applies to each of these six areas: If I insulate, I don't have to heat. If I use daylight, I don't need a lamp.

That doesn't sound revolutionary at all.

In the current debate about the coming winter, you can see that many people are not at all aware that what matters is not electricity, but heat, because half of Germans heat with natural gas and a quarter with oil. Three quarters heat with fossil fuels. That is the key German problem. If we weren't discussing natural gas consumption but heat services, we would have a much more fruitful debate about what needs to be done and what not.

Also, many people don't know that turning the heating down one degree can save seven percent on energy. These are orders of magnitude that really cost money, but also have a very serious background: many people have been cold in recent winters. In France, official studies show that one in five households are classified as low-energy and say they felt cold on at least one day in winter 2021.

Because people can't afford heating?

Because they cannot afford to use it and the building stock in France is much worse insulated than in Germany. But we have to keep this in mind: it's easy to tell people to tighten their belts or turn down the heat. But what about the people who already have to decide every day whether to spend their money on food or on heating? They are dependent on emergency programs that are based on heating requirements.

So we have to stop talking about gas, oil and electricity and start talking about heat, light and cooking? So ask: When do we need which energy for what? And not just say: We have to save energy everywhere?

It is exactly like that! What is the purpose of burning gas? What's the result? These questions should be omnipresent, not kilowatt hours or cubic meters of gas. We're just realizing that energy costs an insane amount of money, we're talking about insane sums. The question then is: What are the options? What can I achieve with a given chunk of money I spend today to provide heat, light, communication and mobility?

And if families have to look twice at what they buy in the supermarket, it would be best if they didn't have to spend any money on heating at home because their apartment is insulated and no longer cools down.

In France, energy costs are massively subsidised, with low incomes up to 60 percent of the electricity bill being paid. This is madness. If you take the money and renovate the houses instead, consumption drops dramatically, people's well-being increases and, of course, the bills keep coming down, not just once.

Why isn't this done?

It's not like nothing is happening at all. In Frankfurt, the Klinikum Frankfurt Höchst has just become the first hospital to be certified according to the passive house standard. There is a significant reduction in energy consumption because the building is super insulated with triple glazing and so on. The ultimate. However, all waste heat is also used. All the people who work there, all the patients and every piece of equipment emit heat. You can use that, then the consumption goes down dramatically.

Do people shy away from building passive buildings because the energy industry loses revenue as a result?

Of course, the energy producers have an interest in selling their energy. But it is also easier for politicians and stakeholders of all kinds to imagine that one produces and one consumes. It's easier and more tangible to talk about a solar panel than insulating material. Of course, you also have to say: If you want to change something structurally, you have to go into the existing structure. In new construction, the renewal rate of the buildings is so low that it would take decades to reach a good level.

So you should renovate all old buildings and subsequently insulate large areas?

Yes, there are also really great model projects in various European cities where entire parts of the city are being thoroughly renovated. There, the energy consumption then drops by at least 40 to 50 percent, sometimes even by up to 70 percent. This is not technically feasible everywhere, but you can go that far.

What would be the maximum that could be saved by using energy intelligently?

It is technically possible today to build plus-energy houses. They generate more energy than they consume because they have solar panels on the roofs or facades. But at the Klinikum Frankfurt Höchst, for example, no solar panels were built on the roof because there is a helipad there. That's a good example of "intelligent". You always have to think about the competition. A roof area is now limited. If you want to generate energy there, but at the same time you want daylight to flow in, you have to make it clear from the start what the priorities are, what you can do most efficiently.

But what is no longer possible is space not to be used at all? We probably don't have enough for that.

Yes, of course. Then we end up with multifunctionality, with hybrid solutions. In agriculture, for example, there are phenomenal advances in agri-photovoltaics. This means that the panels are mounted on agricultural levels at a height of around three meters. Then you can still keep sheep or cattle or grow agricultural products underneath. With the rising temperatures, the plants naturally also protect against direct sunlight in summer and strengthen growth thanks to their shading. In the first research results from France, such areas yield 40 percent or even twice as much harvest.

Do you have any other examples of thinking about this type of energy use systemically and on a large scale?

Many large companies are engaged in their lighting. Boeing, for example, rebuilt its kilometer-long assembly line because someone had calculated that switching to daylight could save an insane amount of energy and money. However, with projects like this it also came out that the number of sick days in the workforce has fallen and productivity has risen by 15 percent. The conversion would have paid for itself after three or four years based on the energy savings alone. Due to the side effects, the payback period has shrunk to a few months.

Because people work better in daylight?

Yes. People feel better in daylight, so they work better, make fewer mistakes and get sick less often. There are also retail examples: Walmart, the world's largest supermarket chain, compared daylight stores to those that are artificially lit. Many supermarket chains have fantastic roof areas for it. The result was: Not only do the employees feel better and you save an incredible amount of energy - 40 to 60 percent - but the customers also felt better. What do customers who feel better do? They buy more, up to 40 percent at Walmart. There are so many examples showing that daylight makes sense, including in schools. Then children learn better. And if one works and learns better in daylight, feels better and it is cheaper, one should rebuild all offices, schools, workshops, shops.

Before daylight lamps are purchased for the office to improve employee motivation, mood and well-being.

Incidentally, these daylight lamps are very expensive and only approximate sunlight. It is still not technically possible to imitate daylight. Another argument for daylight.

Clara Pfeffer and Christian Herrmann spoke to Mycle Schneider. The conversation has been shortened and smoothed for better understanding.