For months, Schwedt worried about the future of the PCK refinery. The plant with 1200 employees is something like the economic heart of the Brandenburg Oder region. From twelve million crude oil, the plant produces gasoline and diesel, heating oil, kerosene and other products for the entire Northeast. With the oil embargo against Russia decided to take effect on January 1, the prospects for the plant seemed bleak. But there should be a solution.

In the morning, the federal government announced that it would place the Russian majority owner of PCK under trusteeship of the Federal Network Agency - to be precise, Rosneft Deutschland GmbH and RN Refining

1. The initial situation: Russian operator processes Russian oil

The PCK - formerly VEB Petrolchemies Kombinat Schwedt, hence the abbreviation - has been supplied with Russian oil via the "Druschba" pipeline for decades. A good 54 percent of it belongs to the subsidiaries of the Russian state-owned company Rosneft. He originally wanted to buy the 37.5 percent stake from the co-owner Shell, but this was stopped.

When Russia invaded Ukraine at the end of February and the European Union later decided on the oil embargo against Moscow, the German government faced two problems: PCK was dependent on Russian oil and a Russian operator was in charge. According to Federal Economics Minister Robert Habeck, he had no interest in turning away from Russian oil.

2. Habeck's solution sketch

Habeck went to Schwedt in early May and even then outlined a solution for PCK: deliveries of non-Russian oil via alternative routes; federal financial aid; and a possible trust structure in place of the previous operator, Rosneft. Habeck's State Secretary Michael Kellner later formulated a location guarantee: The PCK would continue to work in 2023 without oil from the "Druschba" pipeline.

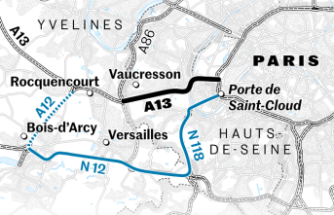

However, it remained unclear whether it would be fully utilized. Because initially, according to the Federal Ministry of Economics, only up to 60 percent of the oil requirement can alternatively be covered via the Baltic Sea port of Rostock. If parts of the plant were broken, not only jobs would be in danger. There would probably also be a lack of regional fuels in the short term. So months have been spent trying to fill the gap. Rosneft suggested buying Kazakh oil. Habeck, on the other hand, was targeting tanker oil from the Polish port of Danzig. The problem: During the war, Poland apparently had no interest in supplying the Russian state-owned company Rosneft.

3. The state steps in

Habeck spoke early on of a trust solution. This is exactly what is happening now with the trust administration by the Federal Network Agency for six months. The legal foundations were laid in mid-May in the Energy Security Act. To secure the supply, this provides for "the possibility of trusteeship over companies in the critical infrastructure and, as a last resort, the possibility of expropriation," as the Bundestag announced at the time.

The government's intervention in PCK was nevertheless delicate for the federal government. For a long time it was feared that Russia would cut gas supplies via Nord Stream 1 in retaliation. Moscow did anyway. Then there was concern that Russia would also stop oil supplies immediately, without waiting for the EU oil embargo. This danger could persist.

4. What does the announcement by the federal government mean?

Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Economics Minister Habeck and Brandenburg's Prime Minister Dietmar Woidke only want to explain the details in the afternoon. The solution should also include a "comprehensive package for the future" for Schwedt. But should Russia stop delivering oil to Schwedt overnight, capacity utilization could drop in the short term until a replacement arrives. As a result, it could become more difficult at times to supply gas stations in eastern Germany. It would be possible to cart fuel from western Germany by road or rail.

In any case, delivery is likely to become more expensive, and prices at East German gas stations could rise. The entry of the state and the switch to new sources of supply should demand a lot from the employees in Schwedt. In the medium term, there will be a completely different upheaval anyway: Schwedt is supposed to turn away from oil and produce "green" hydrogen.