Many websites manipulate users in a targeted manner. Some collect as much data as possible, others cheer the unsuspecting about a paid subscription. The tricks are creative, the legal framework is full of holes.

An e-book was for sale, optionally with tips on nutrition, diets or dog training. The offer sounded tempting: price one euro plus shipping costs. At the latest when looking at the next bank statement, the realization came: Something is wrong here. The bill listed the price for a monthly subscription. A subscription that the customer never wanted, but had unknowingly taken out upon purchase.

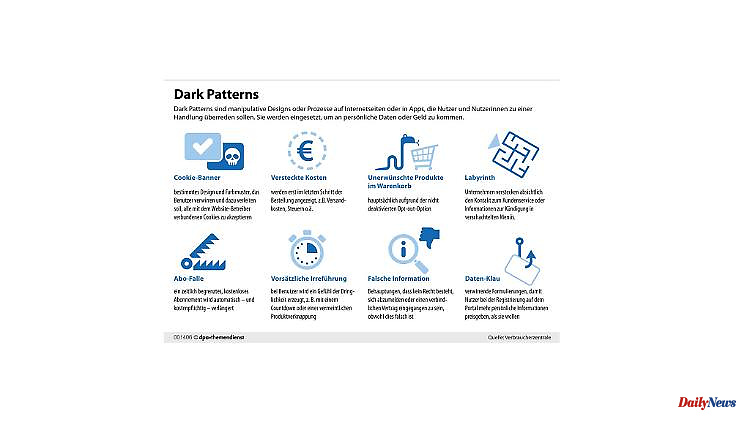

In this case, the way to the subscription trap was via the small print on the website, well hidden between large, colorful areas and buttons that caused distraction. The case is an example of what are known in the jargon as dark patterns: trying to influence a consumer's decision through psychological tricks or manipulative design elements.

The consumer advice center of Rhineland-Palatinate (VZ RP) is receiving more and more complaints about dark patterns, says Jennifer Kaiser, consultant for digital and consumer law: "It started with cookie banners." Users complained about the obtrusive and often confusing windows in which data protection settings had to be made when visiting a new website.

Now, above all, people who can no longer find a way out of the subscription trap are reporting, says consumer advocate Kaiser. Because even after the unwanted conclusion of a contract, dark patterns "help" to confuse consumers. For example, by companies or retailers hiding the contact to customer service or information about cancellation in the shallows of menus.

One thing is clear: dark patterns are omnipresent. "Every second cookie banner in Germany contains dark patterns," says Peter Hense, lawyer for IT and data protection. Since December 2021, it has been legally regulated that cookies may only be set if the user "has consented on the basis of clear and comprehensive information". Exactly what that means, however, is a matter of interpretation. When in doubt, the only way is often to go to the consumer advice centers, which regularly complain.

It is important not to be pushed or intimidated. "Some companies cheekily claim that they have agreed," says lawyer Hense - only because the consumer accidentally clicked on a certain option. But that doesn't necessarily hold up in court. Others try to make customers believe that revocation is not possible, reports consumer advocate Kaiser. For online purchases, however, a 14-day right of withdrawal is the rule.

Website providers use various tricks to get customers to behave in a certain way. Example cookie banner: "The more privacy-friendly alternative is placed peripherally and visually inconspicuously," explains Professor Frank Kargl from the University of Ulm. And if you don't want to share your usage data while surfing on a site, you have to fight your way through umpteen checkboxes and subpages to manually deselect all approvals.

Many give up and accept all cookies annoyed. The banners are designed in such a way that they exploit human automatisms. If you want to get to a page quickly in order to do something, you are more likely to click on the preselected option in a seemingly irrelevant dialog so as not to be stopped, explains Kargl.

Other popular tricks: Shortly before the payment process, an item suddenly appears in the shopping cart that the buyer didn't even put in it. Or certain options, such as taking out travel insurance when booking a flight, are already preselected.

"Sometimes the impression of urgency is given," says Prof. Kargl, for example by a countdown running or a booking portal pointing out in red letters that "only 1 room" is still available. Or users are made to feel guilty: "If you don't fill out all the fields, our service won't be able to show you the best possible result".

The problem: many of these practices are legal. When booking portals state that only a few flights are still available or a limited number of offers, this is "a marketing tool" and therefore legally permissible, explains consumer advocate Jennifer Kaiser. So far, politicians have only intervened to a limited extent.

An intervention by the EU Commission, as in December 2019 with Booking.com, is rather the exception: the booking portal was instructed to make its website more transparent: Offers may only be advertised as limited if they are actually no longer available at a later date .

In order not to fall for the tricks of the providers, consumers must above all know them. Examples of dark patterns and pages that use them can be found through search engines. There are several web collections or case studies by scientists that also clarify consumer advice centers.

Otherwise, what helps above all is: be attentive, don’t click on buttons too quickly, check the wording carefully and check the shopping cart and the total sum again before purchasing a product. Because dark patterns only work if they really stay in the dark.