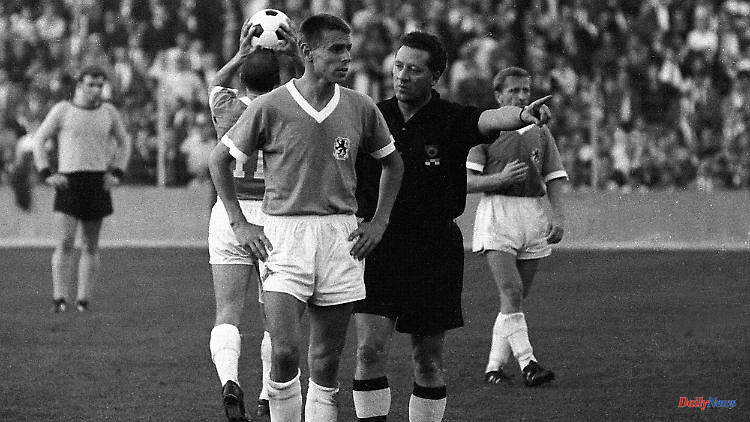

1966/67 season: Incredible scenes take place in early October 1966 in the TSV 1860 Munich stadium. Striker Timo Konietzka is angry about a referee's decision and attacks the referee in an unusual way. This will result in a long ban.

Timo Konietzka's mother Emma knew no mercy. If a teammate got too close to one of the three Konietzka brothers on the soccer field, she would run onto the field and beat her sons' disobedient opponents with an umbrella. The legendary Bundesliga player Friedhelm Konietzka, whom everyone just called Timo, must have unknowingly had this behavior in his genes. The TSV 1860 Munich striker was certainly not a child of sadness in the 1966/67 season. Unfortunately, that was also evident when on October 8, 1966, the eighth day of the season, his sixties played his former Borussia from Dortmund at home.

When Konietzka disagreed with a decision made by referee Max Spinnler, he pushed the referee in the chest, angrily ripped the whistle out of his mouth, stomped on it and finally kicked Spinnler in the shin. Konietzka later said - still not very insightful and furious - that he only kicked the man in black "a little bit" with his cleated shoes. Be that as it may: Konietzka received a sentence that was to be the longest for a Bundesliga professional for many years. The attacker had to sit out six months. The DFB knew no mercy. Probably also because Spinnler had to be escorted out of the stadium under police protection after the game.

In the championship fight, after SV Werder had won the title two years earlier, there was the second really big surprise in the four-year history of the Bundesliga. Nobody had the new German champions Eintracht Braunschweig on their list before the season. Fritz Walter, the 1954 World Champion in Kaiserslautern, even predicted that the Lower Saxony club would be relegated and then had to apologize, as did Eintracht's own coach. Helmut Johannsen had predicted a maximum of sixth place in the table. Looking back, the conditions weren't all that bad.

Since 1963, Helmut Johannsen had continuously built up his team according to his ideas. In the championship year he was the only coach in the Bundesliga who had been employed by his club since the start of the new elite league. It was now paying off. Almost the entire team played through. Ten players had more than 30 missions. After winning the title, Johannsen said a sentence, not without reason, for which he was smiled at in Germany: "It wasn't a miracle. It was hard work!"

In general, the championship of harmony among experts was more of an undeserved sensation. The former publisher of "Kicker", Dr. Friedebert Becker even said that the title was "won by the wrong person". Only a few were able to recognize Eintracht's class like Bayern coach Tschik Cajkovski after his Munich team lost 5-2 in Braunschweig: "The opponents played like world champions!"

Gunther Baumann, the third coach this season at 1860 Munich, also saw the advantages of the German champions: "Braunschweig's team fits together more harmoniously than any other." And this harmony was homemade. They were modest at Eintracht, paid attention to the collective and didn't make any big leaps when choosing their players. All but one came from northern Germany - even the most prominent signing, Hanoverian striker Lothar Ulsass. The star player's commitment paid off. He scored 15 goals in the championship year for Eintracht and was also very important for the squad in other ways, as Helmut Johannsen once said: "Lothar Ulsaß was our bright man, who had a positive influence on the entire team and was always up for a joke. Even outside of the field, he represented a personality respected by everyone." Hard work was done in Braunschweig, consistently, but only four days a week and never in a training camp - the Eintracht coach didn't think much of them: "No one learns football from Monday to Friday. At most, he becomes a good skat player."

In one point, however, the critics had to be right: Braunschweig played an unexcited, unspectacular, but very consistent season. Up until the 28th match day, they only conceded three goals at home. In total, the goalkeepers Horst Wolter and Hans Jäcker only had to get behind them 27 times, for comparison: The next best defense team came from Dortmund and conceded 41 goals against them. However, Eintracht only scored 49 times. Helmut Johannsen described the criticism of his tactical orientation as follows: "Winning the championship also depends on the total number of weak games. And in this respect, our balance sheet really bears any comparison."

This season, Germany also celebrated its new "bomber of the nation": Gerd Müller. Up until matchday 28 it looked as if the Bayern striker would become the sole top scorer, but then he failed to find the net for 467 minutes. Lothar Emmerich scored the two goals against Bayern on the last day of the game that he was still missing from Müller. And so the two strikers shared the goalscoring cannon. But only the young talent Gerd Müller was named "Footballer of the Year".

The most unusual game of the season took place on November 12, 1966 in Dortmund. On this day, the fog in the Rote Erde arena suddenly became denser and denser. In the game between Borussia Dortmund and FC Schalke 04, the score was already 4-0 at the break when the view suddenly disappeared on this cold, wet autumn day. It was a derby that those present will never forget. BVB player Theo Redder could only watch that day: "I had a friend from Wickede with me and we laughed our heads off because you couldn't see anything anymore. There was only fog." Other visitors didn't look as patiently at the no longer recognizable playing field as the "Rundschau" reported at the time: "Various people went for a beer, others regretted that they hadn't packed a deck of cards, and the smartest made their way home."

Referee Henning just let the game continue and even had a coherent explanation ready: "Whenever the ball was shot into the fog, I ran after it and was there when the ball came down. That was exhausting, but still okay." And the players? Klaus Fichtel remembers: "I was in close contact with Norbert Nigbur at the back. We were surprised that things kept going on. You had to inform each other about the score." Fog or not, the match ended 6:2 for Borussia Dortmund. However, how the four goals were scored in the second half will probably forever remain a secret for the few people directly involved.