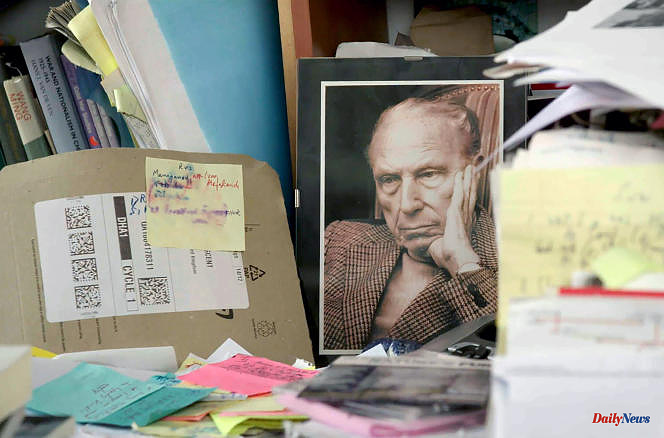

In the introduction to his Conversations with Douglas Sirk, historian Jon Halliday recalls that the filmmaker had told him that the studio for which he had filmed All that Heaven Allows (1955) had understood its title backwards. "As far as I'm concerned, heaven is petty," the master of Hollywood melodrama and Technicolor pessimism will dryly comment.

The formula says a lot about the art of the German filmmaker (1897-1987), born Hans Detlef Sierck, to whom Roman Hüben pays homage in the documentary Douglas Sirk, the filmmaker of melodrama (2021). Because if predominate in his films the flamboyance of the colors, the radiant artificiality of the decorations, the sentimental permanence of the music (by Frank Skinner, his favorite composer), darkness is the major tonality of Sirk.

By a subtle reversal of moral values, his strong characters are "weak": "bad" mothers and "bad" daughters, blondes in distress, depressed aviators, alcoholic heirs believing themselves to be infertile, depressed who ignore themselves, etc. They redeem themselves or expiate their faults in bittersweet, even tragic halftone "happy endings" - like the conclusion of his last film, the sublime Mirage of Life (1959).

Sirk did not only shoot melodramas and, among those he produced, a significant part is indebted to his first career, in Germany, which he left quite late, in 1937, in the company of his second wife, Jewish. He leaves behind the first, who has become a Nazi, and his young son, who will die on the front at the age of 19 after showing his beautiful face in propaganda films.

Autobiographical palimpsest

Roman Hüben rightly dwells on this intimate drama which Sirk will never talk about, except to Jon Halliday – who intervenes in the documentary – by making him promise not to reveal his words until after his death. What the historian will do in a revised and expanded version of Sirk on Sirk, in 1997 (published the same year in French by Cahiers du Cinéma).

It is also recalled how the plot of the film The Time to Love and the Time to Die (1958) is an autobiographical palimpsest. Shot in Germany, in a natural setting of real ruins (which, of course, look more fake than life), the film tells, without anyone knowing it at the time, the tragic story of Klaus, the young son whom Sirk was never going to see again.

Jean-Luc Godard had devoted a resounding article to this last film, Tears and speed, in Les Cahiers du cinema of April 1959; ten years later, Rainer Werner Fassbinder also contributed to the rehabilitation of Sirk, too often mocked for his gleaming lacrimal expression machines.

Roman Hüben quotes what Fassbinder said about the genius of Douglas Sirk and recalls that he had invited his eldest to teach at the Munich film school and to supervise short films shot there between 1975 and 1979, when that Sirk had returned to Europe (he lived in Lugano, Switzerland, until his death).

Another "disciple" to intervene in this interesting documentary, the American Todd Haynes, who, in Far from Heaven (2002), subtly took up the dramaturgical and visual codes of the great filmmaker whom he too admires so much.