On August 15, 1943, an American fighter plane appeared over the town of Villalba in northwestern Sicily. A yellow flag with a black “L” fluttered out of its cockpit. A bag fell from the machine, in which the owner of the nearby homestead also found a yellow cloth with an “L”. Shortly thereafter, three US tanks reached the city, one of which also carried such a flag. An officer got out and asked for "Don Calò" in Sicilian dialect. A man then appeared, showed the cloth from the bag that had fallen, and climbed into the tank. His name was Calogero Vizzini, the supreme godfather of the mafia in Sicily.

This is how the cooperation between Cosa Nostra and the Allies is said to have started when they opened a first “second front” in Europe against Mussolini and Hitler in the summer of 1943 with the invasion of Sicily. It is said that the “honorable company” served them well. "Don Calò", for example, would have persuaded the Italian garrison of the important position on Monte Cammarata to flee and at the same time assigned an underboss to lead a US column. The strange alliance was engineered by the man with the big "L": Lucky Luciano. Although the New York mafia boss was in US prison, his name opened every door in Sicily.

A rich story that is still loved to be told. It's just a pity that it's wrong, writes the historian Thomas Vogel in his book "The Second World War in Italy 1943-1945" (Reclam, 160 p., 14.95 euros). The scientist at the Bundeswehr Center for Military History and Social Sciences in Potsdam refers to numerous testimonies and facts that have exposed the episode as a rumor. Nonetheless, the story has a kernel of truth. A real collaboration developed between the United States and the Mafia during World War II, well after the invasion of Sicily.

As early as spring 1942, US authorities had discreetly asked the mafia for help. It was the climax of the Battle of the Atlantic. German U-boats lurked off the American east coast and sank numerous Allied ships. And the Italian-born workers in the ports were suspected of supporting them with information or even acts of sabotage.

True, Lucky Luciano, the godfather of godfathers, had been in prison since 1936. But he was happy to use his criminal network to protect democracy by keeping his people in the ports. Spies were not unmasked, but idleness or even strikes were now a thing of the past. For ease of contact (and arguably thanks) Luciano was transferred from Dannemara State Penitentiary to New York's Great Meadow Prison, closer to the coast.

After the surrender of the German-Italian Army Group Africa in Tunisia in May 1943, the Allies set their sights on Sicily as the next target. The large island seemed far enough from the centers of Hitler's "Fortress Europe" that limited defenses could be expected. The Americans and British also no longer rated the Italians' willingness to fight very highly. And the Wehrmacht had drawn up all the reserves for their summer offensive on the Eastern Front, aimed at the Kursk Bulge.

From this, the Allied leadership concluded that an American and a British-Canadian army would be sufficient to successfully carry out "Operation Husky", the landing in Sicily. The new Allied commander-in-chief, US General Dwight Eisenhower, did not want to use more, since all available resources were needed for the planned landing in northern France.

Above all, the US naval intelligence service ONI had no problem getting information about Sicily from Luciano and his people. Although his offer to go home himself and set up a spying and support organization there was "politically too delicate for those responsible," writes Vogel. "Instead, ONI assembled a team of Italian-speaking officers who went ashore with the first wave at Gela and Licata on July 10, 1943."

They had been provided with contacts where they could count on local guides or scouts. Mafiosi were only too willing to do this, as they had had a difficult time under Mussolini's fascist dictatorship. The dictator persecuted them with a severity they were not used to. The population also hated the fascists. Tired of the war and its hardships, she saw liberators in the soldiers from America, where two million Sicilians had emigrated. The fact that the checks from her former compatriots had been an effective remedy against the rampant poverty did the rest.

The rapid advance of the 7th US Army under General George Patton, which marched into Palermo on July 22, is often cited as an argument for good cooperation between US troops and the mafia. The British 8th Army, on the other hand, needed five weeks to advance from their landing sectors in the south to Messina. However, Thomas Vogel finds three reasons that have nothing to do with organized crime.

First, on July 11, Hitler gave up his restraint and ordered an armored and paratrooper division onto the island, halting the British and Canadian advance. Second, their commander-in-chief, Bernard Montgomery, deviated from the plan of operations by dividing his army and advancing not only on Catania, but also west of Mount Etna. Thirdly, this was possible because the Allies had failed to install a joint high command for "Husky". The result was "that the main attack 'starved' off Catania," concludes Vogel.

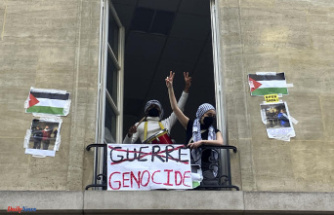

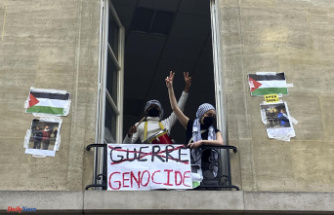

The Mafia began to rise again immediately behind the front. The fascist officials were deposed and arrested, while masses of shaven-headed mafiosi poured out of the prisons, posing as the regime's persecutors. "In addition, the conservative 'men of honor' received a good reputation through natural allies in the fight against communists and socialists," writes Vogel: "the Catholic clergy, which was itself infiltrated by the mafia".

Godparents often enough replaced Mussolini's governors. Calogero Vizzini, for example, the "Don Calò" from Villalba, was appointed mayor of his city by the US military and also made honorary colonel. He took advantage of his new position to reestablish his power in breakaway areas of his old dominions.

The Allies could not prevent the successful retreat of the German combat troops from Sicily. But after landing on the Italian mainland in early September 1943, the military government was faced with the unpleasant task of ensuring order on the island with the few remaining units. The Mafia was happy to fill in the gaps that arose.

Precisely because Italy remained a secondary theater of war to the end, she had a rich field of activity. After Allied troops took Naples in October, Camorra's godfather, Vito Genovese, who had supported Mussolini up to that point, immediately switched sides. He served as an advisor to the head of the Allied Control Commission for Campania.

This Charles Poletti was of Italian descent and had been a civil lawyer and politician. "Although there is much to suggest that he was culpably involved in Genovese's criminal activities, it has never been proven," writes Vogel. They were significant. Within a very short time Genovese built up one of the largest black market organizations in southern Italy. About a third of the Allied supplies routed through the main base in Naples are said to have disappeared down dark channels. Genovese's most important partner is said to have been "Don Calò" Vizzini.

After Genovese was arrested and relocated to the United States in 1945, another boss took over the business. After the war, Lucky Luciano was pardoned by the governor of New York and deported to Italy. Now he built up a transatlantic distribution network for drugs and other illegal businesses. This was to prove a heavy burden for the democracy that the Allies had restored to the Italians.

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.