France Culture, 2019. Christine Lecerf, with her talent, plunged us, for ten hours, into “the depths of the night” by Louis-Ferdinand Céline (1894-1961). Throughout this “Great Crossing”, historians, writers, actors and Celinians questioned the Céline case.

This is because, more than half a century after his death, the man who was born Louis Ferdinand Destouches divides: in 2018, Gallimard gave up publishing his anti-Semitic pamphlets, which, as Serge Klarsfeld, founder of the association, would then recall Sons and daughters of Jewish deportees from France, “had an important and criminal role”.

Since then (end of summer 2021), six thousand unpublished pages, including three novels and what Céline himself calls “the Jewish file”, have resurfaced. Gallimard published one of these texts: Guerre (2022), in an edition established by Pascal Fouché with a foreword by François Gibault, which in no way mentions the pamphlets.

It is in this context that Philippe Collin decides to “submit the destiny of Céline to the gaze of historians”, explains in the preamble the journalist who devoted a series to Philippe Pétain and another to Léon Blum, in 2022. Let us recall here what Céline wrote in 1937: “I say it quite frankly, as I think, I would prefer twelve Hitlers rather than one omnipotent Blum. »

More radical than Vichy

Therefore, asks Collin, “what place does the sulphurous writer occupy in our collective memory? A genius stylist (…), Louis Destouches nonetheless remains a virulent and radical anti-Semite, a patented racist and pro-Nazi, who worked for the moral and political bankruptcy of the Vichy regime.” Through numerous archives and relying on the great historians of the period, Philippe Collin gives us to understand what the writer embodies in French society yesterday and today.

The first episodes return to known facts: his birth in Courbevoie (current department of Hauts-de-Seine), his engagement in the First World War, his injury, his thesis on Semmelweis, the publication of Voyage au bout de la nuit in 1932 and the failed Goncourt.

If, after the Shoah, Céline relied on his pacifism to justify his anti-Semitism, he was nevertheless very much a collaborationist. Thus, in Les Beaux Draps, he uses a footnote to say: “By Jew I mean any man who counts among his grandparents a Jew, only one. » Or Les Beaux Draps was published in February 1941, a few months after the “first statute of the Jews”, a decree-law which “regards as Jewish any person descended from three grandparents of the Jewish race or from two grandparents of the same race. race, if his or her spouse himself is Jewish.” Céline is therefore more radical than the Vichy regime. Historians remind us that “words are performative”: “Anti-Semitism of pen becomes anti-Semitism of action” (fascinating episodes 6 and 7).

Scientific precaution

The eighth episode shows how, from Copenhagen, where he fled, Céline “weaves his web of innocence” (Philippe Collin). Then how, after having benefited from a "dubious amnesty" (as asserted by Anne Simonin, who worked on the archives of the writer's trial), Céline will insist, on her return to France, on her status as a "victim of the purification policy”.

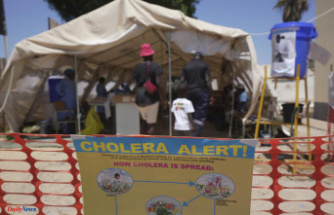

The last episode raises, in particular, the question of the republication of the pamphlets – which Céline's descendants refuse, even if, remember, they are readable online and they will fall into the public domain at the end of 2031, thus giving the possibility for anyone to republish them without scientific precautions. Historian Odile Roynette asks, concerned: “How is it useful to republish texts of such violence in the very complicated context of intolerance towards the growing Jewish community? »

Finally, what can we say about the large corpus – these 6,000 unpublished leaflets which disappeared at the time of the Liberation before reappearing in 2020 – which remains unusable by researchers, which everyone regrets? For Anne Simonin, “Céline is interesting because it symbolizes a way that the French had of not wanting to see how far they had gone when they accepted the German policy of collaboration.” And added: “My interest in the Céline case is also how we tell ourselves stories and how we end up believing them. »

For Philippe Collin, no doubt: “We told a lot of stories about Céline; and, since it is said that he is the greatest French writer of the 20th century, I was interested in knowing who he is while trying to escape from the fable. Doing history is trying to get closer to a scientific truth. »