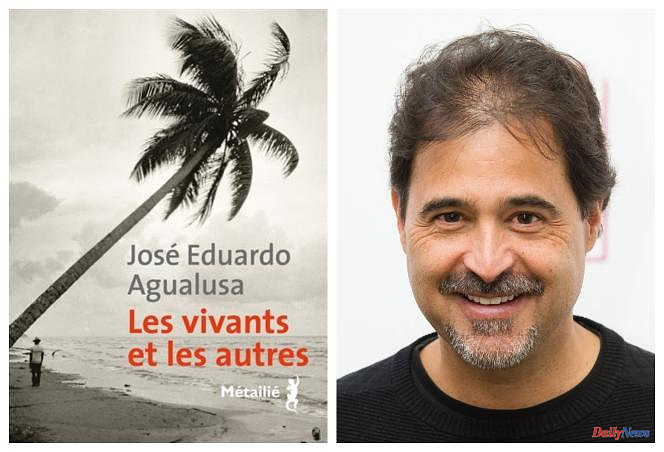

The frame was almost perfect. The island of Mozambique, off the eponymous country. Popular authors from all over Africa and its diasporas. On stage and in their hotels, they discuss the books and colonial history they share, the future of the continent, ghostwriters and forbidden works that have become cults. If the literary festival imagined in The Living and the Others by José Eduardo Agualusa seems idyllic compared to the events organized in France, the device remains that of a scientific experiment - or rather philosophical, as the poem at the beginning of the novel suggests:

"This is how it all begins: the night splits into an immense glow, and the island detaches itself from the world. One time comes to an end, another begins. Nobody, then, realized it. »

What happens to authors if they are pulled from their desks to speak in front of an audience and sign their books for days on end? Ask the characters of this novel, real (Gonçalo M. Tavares, Sami Tchak, Fatou Diome, Breyten Breytenbach) or invented. Among the latter are the former Angolan journalist Daniel Benchimol and the Mozambican artist Moira, at the initiative of the festival. The couple appears in Agualusa's previous book, The Society of Involuntary Dreamers (Métailié, 2019), of which this new opus would be an island sequel.

No more internet or phone

An invention too, Ofélia Easterman is a poet born in Angola who grew up in Lisbon before settling in Rio de Janeiro. The first time it appears to us like this:

“Ofelia Eastermann wakes up, four verses dancing in her head: “After midnight, on Fridays, /Ofelia sewed infinity in the sky. /Meanwhile, the breeze was gliding between the palm trees, /a river-rumor of spirits.” She gets up and writes them down in a small notebook with a red cover, on which she has written in big black letters: “Dreamlike trash can .” »

Ofélia's nomadism makes her allergic to any question about where she belongs. His famous line - "I'm from where the damn palms are!" – adorns t-shirts that earn him more than his writings.

Finally, Cornelia Oluokun. This American-Nigerian conquered a large audience with The Woman who was a cockroach. She is now struggling to begin her great novel on Africa announced in the press. Annoyed by an albino child spying on her and the state of "ruin" of the city, Cornelia wants only one thing: to flee. Impossible. A storm hit the island of Mozambique. Those who cross the bridge to the mainland do not return. No more Internet or telephone, rationed electricity. Height of anguish, Moira is about to give birth.

Between fantasy, dream and reality

"Almost" is the word that best sums up the aesthetic of the novel. Nothing is ever sure here. The end of the world may have arrived, but the literary encounters continue. The guests continue to write, read each other's books and tell each other stories, challenging themselves to tell the real ones from the fake ones. Little by little, the heat and the ocean liquefy the boundaries between fantasy, dream and reality. After all, "the real is just a by-product of fiction," wrote one guest.

José Eduardo Agualusa, who lives between Rio, Lisbon and Mozambique since his political positions rendered him persona non grata in Angola, is not composing here an African version of Boccaccio's Decameron. In this collection of 100 short stories written in the 14th century, the narrators fled the Black Death for an earthly paradise from which they will have to distract themselves by improvising storytellers. Here, the novelist, poet and journalist is interested in the creative process, from inspiration to constant uncertainty. On this island which is no longer attached to the world by any bridge or medium but only by writing, anything can happen. Like hearing voices and seeing fictional characters arrive, some of whom demand accountability from their creators.

While some give in to panic, others redouble their inspiration. "We should always write as if everything is about to disappear," says Ofélia. “When the world is gone, Daniel declares, it will be reborn in the islands. And transformed in the books that contain them, seems to assert Agualusa in this novel bursting with life.