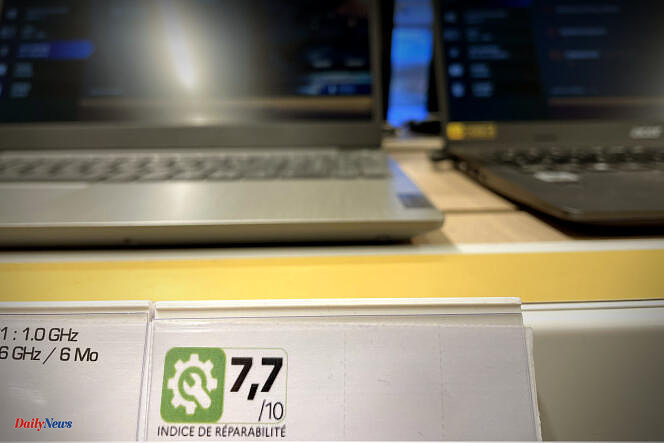

On Wednesday March 20, the Directorate General for Competition, Consumption and Fraud Repression (DGCCRF) shared the results of its second wave of control on the repairability index, a decision-making tool launched at the beginning 2021 in the form of a small colorful label, displayed next to the price of certain electronic devices and household appliances. There is a rating out of ten giving the consumer an idea of the ease with which they can have their device repaired.

During the last three months of 2022, DGCCRF agents checked around four hundred businesses and noted the frequent absence of this label. Above all, they visited a handful of manufacturers, or importers representing them, in order to dissect the bases of their index calculations. Because the repairability rating is not developed by the administration, but by the brands themselves, who assign it to themselves.

In order to carry out their evaluations, DGCCRF agents asked brands to provide evidence justifying the numerous sub-scores which are taken into account in the final calculation. Each corresponds to a criterion such as the price of a spare part (battery, screen, photo sensor, etc.), its availability, the number of steps necessary to disassemble it, etc.

“On this last criterion, we asked manufacturers to provide the report of a dismantling test carried out by an independent laboratory,” explains Hélène Héron, head of the “industrial products” office of the DGCCRF, to Le Monde. In the future, we are studying the possibility of having these declarations verified by a laboratory commissioned by us, but this will not be done before 2025.”

Few manufacturers controlled

The agents supplemented these part checks with field checks, for example assessing the actual availability of spare parts. But no price control of these precious components has been carried out. An investigation by Le Monde, published a few weeks before the campaign, nevertheless established that Apple distributors billed independent repairers for these components at very dissuasive prices, which deprived these repairers, the majority in France, of official parts.

“Manufacturers set their prices freely,” explains the DGCCRF. Our repairability index checks cannot focus on this criterion. This is a competition law issue, which we could only control as part of another investigation into possible anti-competitive practices. » In their 2022 campaign, DGCCRF agents did not visit either Apple, Samsung or Oppo, three manufacturers whose calculations were denounced a few months earlier by the Stop Planned Obsolescence association. .

In total, fraud enforcement visited only three manufacturers or importers, checking notes on twenty vacuum cleaners, four smartphones, nine dishwashers, thirteen computers, seventeen televisions, twenty-two lawn mowers and forty-four washing machines. Each of the manufacturers or importers inspected was found at fault: in two cases, supporting documents were missing, in another, the calculation was distorted. They all sinned on the same type of product: their electric lawn mowers. They received a warning or a compliance order, but none received a fine.

When questioned, the DGCCRF admits that for the moment, the extent of controls on manufacturers and the severity of the sanctions may seem disappointing. However, she emphasizes that these controls carried out on an annual basis are expected to increase in strength: “Training agents takes time,” argues Ambroise Pascal, delegate for the ecological transition of the DGCCRF. As for sanctions, its agents will gradually toughen their tone. The time is still “for pedagogy”.

A significant effort on businesses

At the other end of the chain, businesses were controlled much more widely. The labels were checked in several hundred shops and supermarkets, for a total of thirteen thousand products. The findings of DGCCRF agents are hardly positive: the label was missing for 39% of products, its format was not compliant in 14% of cases. The detailed grid, which mentions a dozen sub-notes for each product, was inaccessible in three-quarters of the cases.

“Very often, the professionals being inspected are either not aware of this obligation, or they are aware of it, but are not able to comply with it. It is impossible for them to know where the details of the calculation of the score are located,” explains the DGCCRF in its report.

As for online stores, the DGCCRF checked around ten sites, a good half of which were marketplaces. Of 1,241 affected products, it found that the label was missing in 46% of cases. The detailed scoring grid was missing in 52% of cases.

Manufacturers, physical stores, online merchants: a total of 523 establishments were checked. Among them, 341 presented an anomaly, 256 received a warning (the same establishment may have received several), 89 an injunction to comply. The DGCCRF has issued five fines of a maximum of 3,500 euros to wholesalers or sellers, all repeat offenders. She also issued a criminal report to a household appliance repairer, a file sent to the public prosecutor.