Telling the story of the past 2000 years in 2000 pictures is a challenge. Draftsman Jens Harder masters them with a symbolically charged flood of images, many associations and a gloomy mood in the face of human history.

In geological terms, 2000 years is a piece of cake. According to scientific calculations, the Big Bang was almost 14 billion years ago and the earth is 4.54 billion years old. The archaic Homo Sapiens arose 300,000 years ago, the first advanced civilizations of modern humans 6000 years ago. In purely arithmetical terms, the past 2000 years or so are only a blink of an eye in history.

And yet the two millennia since the dawn of time form the core of global cultural memory. They are packed with events, developments and inventions, with the rise and fall of empires, with the conquest, exploration and subjugation of the world, with monuments, records - and pictures.

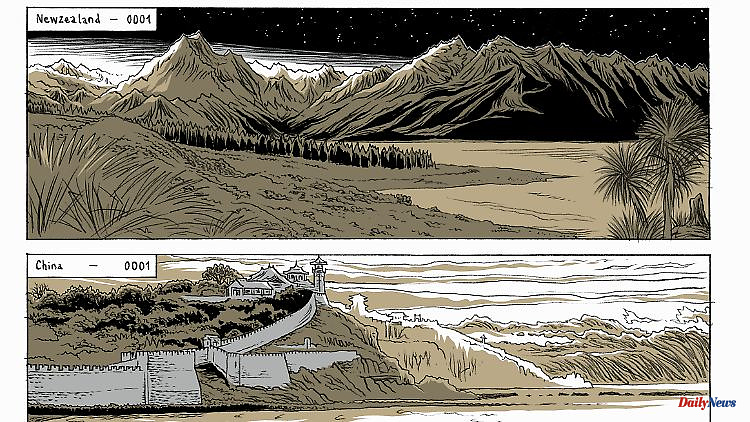

It is all the more astonishing that the comic artist Jens Harder tells the story of those 2000 years on 368 pages, in a good 2000 pictures. The opulent volume "Beta ... Civilizations 2" is the third part in his series about the history of the earth. After "Alpha" (2010) about the time from the big bang to prehistoric man and "Beta ... civilizations 1" (2014) about the development of man up to the turn of the century, he now presents a visually stunning journey through history since high antiquity, like the predecessors were published by Carlsen Verlag.

The artist, who lives in Berlin, remains true to his concept: as a DJ of world history, he mixes his own rhythm from a multitude of graphic representations. In addition to scientific display boards, there are works of art and paintings, photos and video scenes or pop culture references from Charlie Chaplin to the Simpsons: Harder uses the motifs as models, but he traces each individual image in his own style.

The choice of visual material is subjective, but on the one hand Harder is careful to avoid a Eurocentric view, even if this proves difficult not only because of the available material. On the other hand, the flood of images evokes very different associations in readers, allowing different focal points and perspectives. Only rarely does Harder weave in text that offers explanations of important developments here and there. Instead, the draftsman relies entirely on the power of the images and their selection, which, given the mass of material, poses a challenge to the reader.

In principle, Harder follows the development of the past 2000 years chronologically, from antiquity through the Middle Ages to modern times - with all the necessary exaggerations, jumps and omissions. But the book is at its strongest when it breaks the timeline with specific examples, when it focuses on lines of ideas. In this way, the presentation of inventions is combined with the consequences that result from them to this day - from the invention of explosives to the atomic bomb, from the first magnifying glass to the space telescope, from mechanical devices to the mainframe computer.

Or historical developments are commented on by current events, sometimes even contradicted. Pictures of the migration of peoples in late antiquity stand next to a picture of today's refugees - the displacement of people through war and violence occurs in every epoch. The violent beginnings of the Frankish Empire find their dramaturgical climax on a page with Aachen's Karlsbrunnen and the EU flag.

The selection of the images and their arrangement suggest Harder's own attitude to some themes, for example in the criticism of globally active banks, which he contrasts with the beginning of colonialism. In contrast to the two previous volumes, in which the history of the earth is presented primarily as a narrative of progress, in this volume the illustrator repeatedly points out breaks in development: vanished empires, disrupted trade networks, lost knowledge, buried memories.

Scenes about the transience of culture and - so-called - civilization leave a lasting impression. Epidemics such as the plague, which kills large parts of the population, throw societies back centuries, conquests destroy cultural achievements, ideologies destroy existing ideas - it sometimes takes centuries before lost progress can be made. Topics such as colonialism, slavery or racism and National Socialism take up comparatively large space. Despite all inventions, all developments and simplifications of human life, this gives the volume a gloomy undertone.

That applies to the end: "Beta ... Civilizations 2" ends in the computer age from 1945, with nuclear power, progressive globalization and digitization, environmental destruction and climate change. The closer Harder gets to the present, the more detailed the depiction becomes - the 20th century takes up a lot of space. This creates a historical imbalance - why should the GDR appear in such a geological history at all - but in view of Harder's own biography - he comes from Weißwasser in East Saxony - it is understandable.

But Harder isn't interested in an objective, strictly scientific representation of history anyway, like in the comic adaptation of Yuval Noah's bestseller "A Brief History of Mankind." His goal is to stimulate readers through the flood of images, to work out lines of development, to establish connections, to pursue ideas - and to entertain them with ironic inserts. It is to be expected that topics or aspects will have to be left behind.

At the same time, the band cannot completely free itself from traditional ideas. Harder obviously tries to depict women and their perspectives in all eras, but in the end historical male figures dominate in the selection of images - because they very often determined the course of history. It is similar with the Eurocentric view. Harder attaches great importance to the depiction of Asian, African, American or Polynesian cultures. In the overall picture, however, Western images with their great symbolic power predominate, especially in recent times - which is not only due to the lack of traditional depictions of distant corners of the earth, but also to the high recognition value.

Even though Harder has arrived in the present in "Beta ... Civilizations 2", his series does not end there. A fourth volume entitled "Gamma" is already in the works, in which the artist looks to the future. The basis for this should be utopian and science fiction literature and films - with their utopias or dystopias about the future of mankind. If Harder stays true to his line, it will be another visually stunning philosophical excursion.