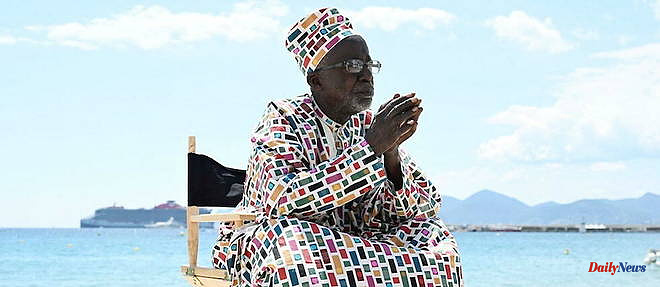

Souleymane Cissé is widely recognized as one of the greatest African filmmakers of all time, and the Cannes Film Festival, the most prestigious in the world, agrees. The Malian-born director has been named winner of the 2023 Carrosse d'or. David Murphy, critic and specialist in African cinema and the work of Cissé, explained to us why his films are so important, in particular his classic Yeelen.

Cissé is a famous Malian director who has been making films since the early 1970s. He was born in Bamako in 1940, but his childhood was spent in Dakar, Senegal, then a neighboring colony of the French empire in West Africa. the West. His father had settled there for his work before returning to Mali after independence in 1960. It was in Dakar that he became passionate about cinema and, from 1963 to 1969, he trained as a director in Moscow. , in Russia, under the supervision of the great Soviet director Mark Donskoy (under whom the legendary Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène had studied a few years earlier).

Cissé has only made nine films in 50 years (and only three since the turn of this century). It must be said that it has never been easy to make a career as a director in Africa (at least outside of the Nigerian Nollywood video industry).

Cissé's reputation is largely based on the quality of the four films he made during the most prolific period of his career, between 1975 and 1987, which culminated with the release of Yeelen (The Light), which won the Jury Prize at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival. It was the first African film to receive such critical acclaim at a festival renowned for its celebration of pioneering new directions in filmmaking.

Yeelen has been hailed by critics not only as a pivotal moment for African cinema on the international stage, but also as the embodiment of a new form of African cinematic practice rooted in the oral storytelling traditions and spirituality of West Africa. the West.

A beautifully directed film, Yeelen tells a mythical and highly symbolic story that pits a rebellious son against his tyrannical father. The film takes place at an indeterminate moment in pre-colonial Africa.

This new cinematic style stood in contrast to the social realism that many critics saw as the hallmark of Francophone West African cinema in the 1960s and 1970s. Sembène's films are generally cited as the most successful examples of this type of work. Cissé himself had been hailed for the social and politically engaged realism of his early films, 1975's Den Muso (The Young Girl) and 1978's Baara (The Work).

With Yeelen, he is now portrayed by many critics as a director who made the "transition" from social realism to a more symbolic, more mystical and therefore more "authentically" African form of cinema.

Yeelen is often cited alongside other films that depict a rural Africa untouched by Western colonial presence, in particular Wend Kuuni (1982) and Yaaba (1989) by Burkinabe directors Gaston Kaboré and Idrissa Ouédraogo.

These films began to be categorized by some critics as films that rejected modernity and the socialist principles of the decades following independence. They are considered to have turned their backs on Western ideas and aesthetics and sought inspiration in an authentic, rural and pre-colonial Africa.

As a film critic, I have never really accepted the various premises that underlie these arguments.

First of all, social realism was never the only dominant aesthetic of the 1960s and 1970s. In fact, it was not even the dominant aesthetic of Sembène's work, to which she was most closely associated with critics. Second, although each of Cissé's early films – Den Muso, Baara, and Finyé (Wind) – may in part be situated in a naturalistic and realistic register, they all feature complex and fairly opaque symbolic sequences.

Cissé lays out his artistic convictions in the magnificent 1991 documentary by Cambodian director Rithy Panh, Souleymane Cissé. He describes the inspiration for his films as an almost dreamlike and visionary process, but firmly rooted in reality. In Finyé, water and wind play this symbolic role in what remains a very political film that denounces the military dictatorship.

I've never been sold on the idea that a specific mode of cinematic storytelling or type of storytelling (rural versus urban, for example) can tap into an "authentic" African identity or culture.

But I fully understand why the quest for authenticity emerged in the 1980s. Dreams of independence had turned into neocolonial nightmares across much of the continent. The directors clearly wanted to express elements of African life that were not considered beholden to the culture of the former colonial powers.

This prize is awarded by the French Association of Directors to reward a filmmaker for the pioneering qualities of his work and the audacity of his cinematographic vision. Previous winners include famous Western directors, including Martin Scorsese and Jane Campion, as well as Cissé's cinematic hero Sembène.

This is an important and deserved reward. Cissé's creativity may have waned in his later years, but the awarding of the Carrosse d'or rightly celebrates a director who, for much of the 1970s and 1980s, was one of the filmmakers the most inventive, not only in Africa, but all over the world. Hopefully this award will inspire more moviegoers to check out his classic films.

* David Murphy is Professor of French and Postcolonial Studies at the University of Strathclyde.