War is not a nationalist phenomenon. It does not only concern the invasion or the defense of a territory, according to which an ideology, for example the fatherland, would be awakened. The landing of June 6, 1944 is an illustration of this. If it begins the Normandy campaign, it is also the conclusion of an intellectual reform of a West in full recomposition. Operation Overlord will have upset the perception that France, Great Britain and the United States had of themselves.

Stalin had been calling since 1941 for the opening of a western front to relieve the efforts of the Red Army. The Americans, who supported England's efforts logistically and financially, hesitated. Roosevelt had to take into account the opinion of an America reluctant to send "boys" to fight across the Atlantic.

As for Churchill, he was not in favor of a landing on the west coast. If the British armies commanded by Montgomery had fought heroically in North Africa, the efforts made were not sufficient to make Germany yield. Despite the successful landing in Sicily in July 1943, the Germans resisted between Naples and Rome. It was not until the Tehran conference that a decision was made, under pressure from Roosevelt and Stalin, for a Channel landing from Great Britain.

As politicians and the military prepared for the offensive, intellectuals in Europe and in the United States were, since the mid-1930s, forced to reinvent themselves. German artists, Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Fritz Lang, Christopher Isherwood, and French artists, Claude Lévi-Strauss, experience exile as an interior revolution.

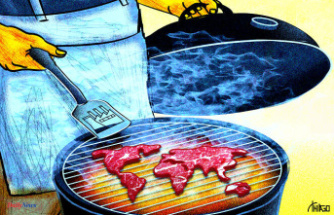

These representatives of the sophisticated elite are forced to admit that deep down Europe and its civilization are no guarantee of anything. This maelstrom will contribute in its own way, mysterious and symbolic, to imagining a new camp: that of a humanity united around the ancient then Christian principle of "just war". Which is not measured by nation or political regime: the alliance with the USSR is the most striking example. This ideology drawn from the origins of Western culture will constitute the basis of the international order founded after 1945. For the first time, Europe had to be conceived outside its borders, exposed to destruction, victim and at the same time guilty of a chaos she had harbored within her: Germany.

The German army they faced was nonetheless also convinced by its deadly ideology. According to historian Jean-Luc Leleu, the Wehrmacht, held as a social group of German society, "supports Hitler or is not hostile to him" to the tune of "60 to 70%"... That's an engaging statistic. Which confirms the new polarization of the Western camp, reinforced by a more than laborious denazification after 1945.

Commemorations are misnamed; their protocol function is negligible. Likewise, the event to which they relate disappears behind the atrocity, the deaths. The heroes of June 6, 1944 not only served an alliance against Nazism, they were the faces of an intellectual and moral rearmament of the West, of healthy reunions between the lessons of Plato, Aristotle and Saint Augustine: The enemies of mankind deserve pure, clean, and thoughtful violence.