The German automotive industry has had a tough few years: Corona crisis, lack of chips, problems with the supply chains - and on top of that the structural change towards electromobility. But things get worse - with the energy crisis. Does this threaten Germany as a car location?

For the German car industry, especially the many small and medium-sized suppliers, the last few years have not been subject to entertainment tax. First came the corona pandemic with global sales slumps, then the global chip crisis with forced plant shutdowns and a thinned out model and equipment program - and finally the Russian war against Ukraine, including Western sanctions against the Moscow regime. But the burdens didn't end there either, because the prices for natural gas, crude oil and electricity exploded.

Above all, the energy crisis relentlessly brought home the high dependence of the German economy on gas and raw material imports. And raised doubts about the quality of Germany as a business location overnight. For example, the President of the Federation of German Industries (BDI), Siegfried Russwurm, expressed his concern that "it is currently about nothing less than ensuring the survival of industry in Germany and Europe". Representatives of Deutsche Bank seconded with gloomy visions: "If we look back at the current energy crisis in ... ten years, we could see this time as the starting point for accelerated deindustrialization in Germany."

And with that, the bad catchphrase: deindustrialization. RWE is planning major investments in the USA, highly energy-intensive traditional companies such as Hakle are going bankrupt, glassware and plastics manufacturers are struggling to survive, as are large parts of the trades, bakers and innkeepers. Is Germany at the beginning of a phase of de-industrialization? Has the descent from the peak of prosperity already begun - and no one noticed? And what role does the automotive industry, parade branch and engine of the German economy play? After all, 20 percent of the German gross domestic product (GDP) and around 10 percent of the industrial added value are generated here. Just as Europe caught the flu when the USA had a cold in previous decades, a crisis in the auto industry is having a similar effect on the German economy today. The 2008 recession is proof of this.

BMW recently announced that the company intends to massively expand its Spartanburg (South Carolina) site in the USA with 1.7 billion US dollars for the production of batteries and new electric models. Six fully electric BMW models are to roll off the production line in Spartanburg by 2030. Is this the beginning of the exodus of the German auto industry and a creeping deindustrialization as a result of the energy crisis?

De-industrialization of an economy was a positive process in earlier parlance. He described the shift in the value-added shares of the individual economic sectors at the expense of industry and in favor of the service sector. This shift was positive and was considered an indicator of the growing prosperity of an economy. To put it simply: all sectors grew, but the industry was so productive even with lower growth that one could indulge in more services. For comparison: In the USA, the proportion of industrial value added has now fallen from 40 percent to around 10 percent of GDP, in Germany it is still around 30 percent.

Today, de-industrialization is understood negatively as a brake on prosperity when the longer-term consequences of the energy crisis are discussed. There is currently a fear that the industrial sector would shrink in absolute terms, either because energy-intensive companies are shifting their production internally to lower-energy plants abroad, or because they are relocating and giving up Germany as a location, or even going bankrupt. The entire service sector would inevitably also be affected.

With regard to the impact of the energy crisis, the auto industry is doubly divided. On the one hand, there are big differences between manufacturers and suppliers when it comes to energy costs in production. For the manufacturers, the cost share of process energy in the total costs is comparatively small (and manageable). The situation is different for small and medium-sized suppliers with rather small-scale production batch sizes and/or a significantly higher production and input share of chemical products and plastics. Since it is often not possible for them to pass on the costs to the manufacturers, the only options are relocation abroad or bankruptcy.

In contrast, the car manufacturers have been hit by the energy price explosion primarily on the sales side. The general opinion is that the German economy is on the way to a severe recession, inflation rates are at ten percent, the highest they have been in decades, and real consumer incomes are shrinking significantly.

Car sales in Germany will be hit hard by this, and instead of the hoped-for market growth, a renewed decline in sales of up to ten percent is likely in 2023. Everyone is affected: domestic and foreign manufacturers.

Relocating production abroad does not help the car manufacturers either, since the sales situation there is often also tense due to the crisis. The danger of emigration due to the high energy costs does not exist in the automotive industry, nor does it exist in the bakery around the corner - it's completely different in the chemical industry.

BMW's planned $1.7 billion investment in Spartanburg is therefore not driven by energy costs and is the beginning of an exodus from Germany. CEO Oliver Zipse: "We are consistently pursuing our principle of 'local for local'. We source our newly developed sixth-generation battery cells here from South Carolina - where the X becomes electric." So there is a strategic expansion in the USA, no crisis-related downsizing in Germany.

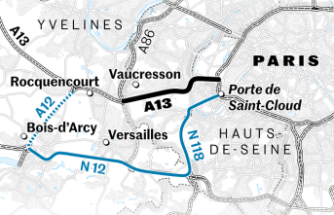

The French President Emmanuel Macron made a similar statement, but from a different perspective, during his recent visit to the Paris Motor Show. Macron wants to make his country a major car nation again as part of the transition to electric cars. The goal is to produce two million electric cars in France every year from 2030, “to make France a major automotive country of the future again”. It is important "to have French production again - for the reindustrialization of the country, for the climate and for France's independence".

Reindustrialization is the order of the day in France. The German car industry has it much easier: Despite the energy crisis, it only has to defend its home location. That seems entirely feasible.